Publication

Editions

Volumes

Vol Titles

Books Table

Resu Table

Prologs Title

Footnote

~-Roadsign that says 'Rainbow Lake 7 miles' with the end of a rainbow directly above it.

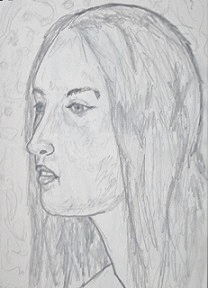

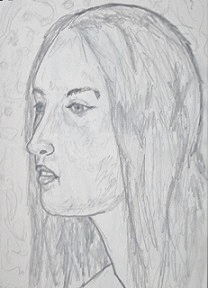

theManofAdamant

@~

@@(Mosses From An Old Manse, by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. The Riverside Press, Cambridge. 1888.)

@#THE INTELLIGENCE OFFICE.

@@Nathaniel Hawthorne

A grave figure, with a pair of mysterious spectacles on his nose and a pen behind his ear, was seated at a desk in the corner of a metropolitan office. The apartment was fitted up with a counter, and furnished with an oaken cabinet and a chair or two, in simple and business-like stye. Around the walls were stuck advertisements of articles lost, or articles wanted, or articles to be disposed of; in one or another of which classes were comprehended nearly all the conveniences, or otherwise, that the imagination of man has contrived. The interior of the room was thrown into shadow, partly by the tall edifices that rose on the opposite side of the street, and partly by the immense show bills of blue and crimson paper that were expanded over each of the three windows. Undisturbed by the tramp of feet, the rattle of wheels, the hum of voices, the shout of the city crier, the scream of the newsboys, and other tokens of the multitudinous life that surged along in front of the office, the figure at the desk pored diligently over a folio volume, of ledger-like size and aspect. He looked like the spirit of a record—the soul of his own great volume—made visible in mortal shape.

But scarcely an instant elapsed without the appearance at the door of some individual from the busy population whose vicinity was manifested by so much buzz, and clatter, and outcry. Now, it was a thriving mechanic in quest of a tenement that should come within his moderate means of rent; now, a ruddy Irish girl from the banks of Killarney, wandering from kitchen to kitchen of our land, while her heart still hung in the peat smoke of her native cottage; now, a single gentleman looking out for economical board; and now—for this establishment offered an epitome of worldly pursuits—it was a faded beauty inquiring for her lost bloom; or Peter Schlemihl for his lost shadow; or an author of ten years’ standing for his vanished reputation; or a moody man for yesterday’s sunshine.

At the next lifting of the latch there entered a person with his hat awry upon his head, his clothes perversely ill suited to his form, his eyes staring in directions opposite to their intelligence, and a certain odd unsuitableness pervading his whole figure. Wherever he might chance to be, whether in palace or cottage, church or market, on land or sea, or even at his own fireside, he must have worn the characteristic expression of a man out of his right place.

“This,” inquired he, putting his question in the form of an assertion, “this is the Central Intelligence Office?”

“Even so,” answered the figure at the desk, turning another leaf of his volume; he then looked the applicant in the face and said briefly, “Your business?”

“I want,” said the latter, with tremulous earnestness, “a place!”

“A place! And of what nature?” asked the Intelligencer. “There are many vacant, or soon to be so, some of which will probably suit, since they range from that of a footman up to a seat at the council board, or in the cabinet, or a throne, or a presidential chair.”

The stranger stood pondering before the desk with an unquiet, dissatisfied air—a dull, vague pain of heart, expressed by a slight contortion of the brow—an earnestness of glance, that asked and expected, yet continually wavered as if distrusting. In short, he evidently wanted, not in a physical or intellectual sense, but with an urgent moral necessity that is the hardest of all things to satisfy, since it knows not its own object.

“Ah, you mistake me!” said he at length, with a gesture of nervous impatience. “Either of the places you mention, indeed, might answer my purpose; or, more probably, none of them. I want my place! my own place! my true place in the world! my proper sphere! my thing to do, which nature intended me to perform when she fashioned me thus awry, and which I have vainly sought all my lifetime! Whether it be a footman’s duty or a king’s is of little consequence, so it be naturally mine. Can you help me here?”

“I will enter your application,” answered the Intelligencer, at the same time writing a few lines in his volume. “But to undertake such a business, I tell you frankly, is quite apart from the ground covered by my official duties. Ask for something specific, and it may doubtless be negotiated for you on your compliance with the conditions. But were I to go further, I should have the whole population of the city upon my shoulders; since far the greater proportion of them are, more or less, in your predicament.”

The applicant sank into a fit of despondency, and passed out of the door without again lifting his eyes; and, if he died of the disappointment, he was probably buried in the wrong tomb, inasmuch as the fatality of such people never deserts them, and whether alive or dead they are invariably out of place.

Almost immediately another foot was heard on the threshold. A youth entered hastily, and threw a glance around the office to ascertain whether the man of intelligence was alone. He then approached close to the desk, blushed like a maiden, and seemed at a loss how to broach his business.

“You come upon an affair of the heart,” said the official personage, looking into him through his mysterious spectacles. “State it in as few words as may be.”

“You are right,” replied the youth. “I have a heart to dispose of.”

“You seek an exchange?” said the Intelligencer. “Foolish you, why not be contented with your own?”

“Because,” exclaimed the young man, losing his embarrassment in a passionate glow, “because my heart burns me with an intolerable fire; it tortures me all day long with yearnings for I know not what, and feverish throbbings, and the pangs of a vague sorrow; and it awakens me in the night-time with a quake when there is nothing to be feared. I cannot endure it any longer. It were wiser to throw away such a heart, even if it brings me nothing in return.”

“Oh, very well,” said the man of office, making an entry in his volume. “Your affair will be easily transacted. This species of brokerage makes no inconsiderable part of my business, and there is always a large assortment of the article to select from. Herein, if I mistake not, comes a pretty fair sample.”

Even as he spoke the door was gently and slowly thrust ajar, affording a glimpse of the slender figure of a young girl, who, as she timidly entered, seemed to bring the light and cheerfulness of the outer atmosphere into the somewhat gloomy apartment. We know not her errand there, nor can we reveal whether the young man gave up his heart into her custody. If so, the arrangement was neither better nor worse than in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, where the parallel sensibilities of a similar age, importunate affections, and the easy satisfaction of characters not deeply conscious of themselves, supply the place of any profounder sympathy.

Not always, however, was the agency of the passions and affections an office of so little trouble. It happened rarely, indeed, in proportion to the cases that came under an ordinary rule, but still it did happen—that a heart was occasionally brought hither of such exquisite material, so delicately attempered, and so curiously wrought, that no other heart could be found to match it. It might almost be considered a misfortune, in a worldly point of view, to be the possessor of such a diamond of the purest water; since in any reasonable probability it could only be exchanged for an ordinary pebble, or a bit of cunningly-manufactured glass, or, at least, for a jewel of native richness, but ill set, or with some fatal flaw, or an earthy vein running through its central lustre. To choose another figure, it is sad that hearts which have their well-spring in the infinite, and contain inexhaustible sympathies, should ever be doomed to pour themselves into shallow vessels, and thus lavish their rich affections on the ground. Strange that the finer and deeper nature, whether in man or woman, while possessed of every other delicate instinct, should so often lack that most invaluable one of preserving itself from contamination with what is of a baser kind! Sometimes, it is true, the spiritual fountain is kept pure by a wisdom within itself, and sparkles into the light of heaven without a stain from the earthy strata through which it had gushed upward. And sometimes, even here on earth, the pure mingles with the pure, and the inexhaustible is recompensed with the infinite. But these miracles, though he should claim the credit of them, are far beyond the scope of such a superficial agent in human affairs as the figure in the mysterious spectacles.

Again the door was opened, admitting the bustle of the city with a fresher reverberation into the Intelligence Office. Now entered a man of woe-begone and downcast look; it was such an aspect as if he had lost the very soul out of his body, and had traversed all the world over, searching in the dust of the highways, and along the shady footpaths, and beneath the leaves of the forest, and among the sands of the sea-shore, in hopes to recover it again. He had bent an anxious glance along the pavement of the street as he came hitherward; he looked also in the angle of the doorstep, and upon the floor of the room; and, finally, coming up to the man of Intelligence, he gazed through the inscrutable spectacles which the latter wore, as if the lost treasure might be hidden within his eyes.

“I have lost”—he began; and then he paused.

“Yes,” said the Intelligencer, “I see that you have lost—but what?”

“I have lost a precious jewel!” replied the unfortunate person, “the like of which is not to be found among any prince’s treasures. While I possessed it, the contemplation of it was my sole and sufficient happiness. No price should have purchased it of me; but it has fallen from my bosom where I wore it in my careless wanderings about the city.”

After causing the stranger to describe the marks of the lost jewel, the Intelligencer opened a drawer of the oaken cabinet which has been mentioned as forming a part of the furniture of the room. Here were deposited whatever articles had been picked up in the streets, until the right owners should claim them. It was a strange and heterogeneous collection. Not the least remarkable part of it was a great number of wedding-rings, each one of which had been riveted upon the finger with holy vows, and all the mystic potency that the most solemn rites could attain, but had, nevertheless, proved too slippery for the wearer’s vigilance. The gold of some was worn thin, betokening the attrition of years of wedlock; others, glittering from the jeweller’s shop, must have been lost within the honeymoon. There were ivory tablets, the leaves scribbled over with sentiments that had been the deepest truths of the writer’s earlier years, but which were now quite obliterated from his memory. So scrupulously were articles preserved in the depository, that not even withered flowers were rejected; white roses, and blush roses, and moss roses, fit emblems of virgin purity and shamefacedness, which had been lost or flung away, and trampled into the pollution of the streets; locks of hair—the golden and the glossy dark—the long tresses of woman and the crisp curls of man, signified that lovers were now and then so heedless of the faith intrusted to them as to drop its symbol from the treasure place of the bosom. Many of these things were imbued with perfumes, and perhaps a sweet scent had departed from the lives of their former possessors ever since they had so wilfully or negligently lost them. Here were gold pencil cases, little ruby hearts with golden arrows through them, bosom-pins, pieces of coin, and small articles of every description. Comprising nearly all that have been lost since a long time ago. Most of them, doubtless, had a history and a meaning, if there were time to search it out and room to tell it. Whoever has missed anything valuable, whether out of his heart, mind, or pocket, would do well to make inquiry at the Central Intelligence Office.

And in the corner of one of the drawers of the oaken cabinet, after considerable research, was found a great pearl, looking like the soul of a celestial purity congealed and polished.

“There is my jewel! My very pearl!” cried the stranger, almost beside himself with rapture. “It is mine! Give it me, this moment! or I shall perish!”

“I perceive,” said the Man of Intelligence, examining it more closely, “that this is the Pearl of Great Price.”

“The very same,” answered the stranger. “Judge, then, of my misery at losing it out of my bosom! Restore it to me! I must not live without it an instant longer.”

“Pardon me,” rejoined the Intelligencer, calmly. “You ask what is beyond my duty. This pearl, as you well know, is held upon a peculiar tenure; and having once let it escape from your keeping, you have no greater claim to it—nay, not so great—as any other person. I cannot give it back.”

Nor could the entreaties of the miserable man—who saw before his eyes the jewel of his life without the power to reclaim it—soften the heart of this stern being, impassive to human sympathy, though exercising such an apparent influence over human fortunes. Finally the loser of the inestimable pearl clutched his hands among his hair, and ran madly forth into the world, which was affrighted at his desperate looks. There passed him on the doorstep a fashionable young gentleman, whose business was to inquire for a damask rosebud, the gift of his lady love, which he had lost out of his button-hole within an hour after receiving it. So various were the errands of those who visited this Central Office, where all human wishes seemed to be made known, and so far as destiny would allow, negotiated to their fulfilment.

The next that entered was a man beyond the middle age, bearing the look of one who knew the world and his own course in it. He had just alighted from a handsome private carriage, which had orders to wait in the street while its owner transacted his business. This person came up to the desk with a quick, determined step, and looked the Intelligencer in the face with a resolute eye; though, at the same time, some secret trouble gleamed from it in red and dusky light.

“I have an estate to dispose of,” said he, with a brevity that seemed characteristic.

“Describe it,” said the Intelligencer.

The applicant proceeded to give the boundaries of his property, its nature, comprising tillage, pasture, woodland, and pleasure grounds, in ample circuit; together with a mansion-house, in the construction of which it had been his object to realize a castle in the air, hardening its shadowy walls into granite, and rendering its visionary splendor perceptible to the awakened eye. Judging from his description, it was beautiful enough to vanish like a dream, yet substantial enough to endure for centuries. He spoke, too, of the gorgeous furniture, the refinements of upholstery, and all the luxurious artifices that combined to render this a residence where life might flow onward in a stream of golden days, undisturbed by the ruggedness which fate loves to fling into it.

“I am a man of strong will,” said he, in conclusion, “and at my first setting out in life, as a poor, unfriended youth, I resolved to make myself the possessor of such a mansion and estate as this, together with the abundant revenue necessary to uphold it. I have succeeded to the extent of my utmost wish. And this is the estate which I have now concluded to dispose of.”

“And your terms?” asked the Intelligencer, after taking down the particulars with which the stranger had supplied him.

“Easy, abundantly easy!” answered the successful man, smiling, but with a stern and almost frightful contraction of the brow, as if to quell an inward pang. “I have been engaged in various sorts of business—a distiller, a trader to Africa, an East India merchant, a speculator in the stocks—and, in the course of these affairs, have contracted an incumbrance of a certain nature. The purchaser of the estate shall merely be required to assume this burden to himself.”

“I understand you,” said the man of Intelligence, putting his pen behind his ear. “I fear that no bargain can be negotiated on these conditions. Very probably the next possessor may acquire the estate with a similar incumbrance, but it will be of his own contracting, and will not lighten your burden in the least.”

“And am I to live on,” fiercely exclaimed the stranger, “with the dirt of these accursed acres and the granite of this infernal mansion crushing down my soul? How, if I should turn the edifice into an almshouse or a hospital, or tear it down and build a church?”

“You can at least make the experiment,” said the Intelligencer; “but the whole matter is one which you must settle for yourself.”

The man of deplorable success withdrew, and got into his coach, which rattled off lightly over the wooden pavements, though laden with the weight of much land, a stately house, and ponderous heaps of gold, all compressed into an evil conscience.

There now appeared many applicants for places; among the most noteworthy of whom was a small, smoke-dried figure, who gave himself out to be one of the bad spirits that had waited upon Doctor Faustus in his laboratory. He pretended to show a certificate of character, which, he averred, had been given him by that famous necromancer, and countersigned by several masters whom he had subsequently served.

“I am afraid, my good friend,” observed the Intelligencer, “that your chance of getting a service is but poor. Nowadays, men act the evil spirit for themselves and their neighbors, and play the part more effectually than ninety-nine out of a hundred of your fraternity.”

But, just as the poor fiend was assuming a vaporous consistency, being about to vanish through the floor in sad disappointment and chagrin, the editor of a political newspaper chanced to enter the office in quest of a scribbler of party paragraphs. The former servant of Doctor Faustus, with some misgivings as to his sufficiency of venom, was allowed to try his hand in this capacity. Next appeared, likewise seeking a service, the mysterious man in Red, who had aided Bonaparte in his ascent to imperial power. He was examined as to his qualifications by an aspiring politician, but finally rejected, as lacking familiarity with the cunning tactics of the present day.

People continued to succeed each other with as much briskness as if everybody turned aside, out of the roar and tumult of the city, to record here some want, or superfluity, or desire. Some had goods or possessions, of which they wished to negotiate the sale. A China merchant had lost his health by a long residence in that wasting climate. He very liberally offered his disease, and his wealth along with it, to any physician who would rid him of both together. A soldier offered his wreath of laurels for as good a leg as that which it had cost him on the battle-field. One poor weary wretch desired nothing but to be accommodated with any creditable method of laying down his life; for misfortune and pecuniary troubles had so subdued his spirits that he could no longer conceive the possibility of happiness, nor had the heart to try for it. Nevertheless, happening to overhear some conversation in the Intelligence Office respecting wealth to be rapidly accumulated by a certain mode of speculation, he resolved to live out this one other experiment of better fortune. Many persons desired to exchange their youthful vices for others better suited to the gravity of advancing age; a few, we are glad to say, made earnest efforts to exchange vice for virtue, and, hard as the bargain was, succeeded in effecting it. But it was remarkable that what all were the least willing to give up, even on the most advantageous terms, were the habits, the oddities, the characteristic traits, the little ridiculous indulgences, somewhere between faults and follies, of which nobody but themselves could understand the fascination.

The great folio, in which the Man of Intelligence recorded all these freaks of idle hearts, and aspirations of deep hearts, and desperate longings of miserable hearts, and evil prayers of perverted hearts, would be curious reading were it possible to obtain it for publication. Human character in its individual developments—human nature in the mass—may best be studied in its wishes; and this was the record of them all. There was an endless diversity of mode and circumstance, yet withal such a similarity in the real ground-work, that any one page of the volume—whether written in the days before the Flood, or the yesterday that is just gone by, or to be written on the morrow that is close at hand, or a thousand ages hence—might serve as a specimen of the whole. Not but that there were wild sallies of fantasy that could scarcely occur to more than one man’s brain, whether reasonable or lunatic. The strangest wishes—yet most incident to men who had gone deep into scientific pursuits, and attained a high intellectual stage, though not the loftiest—were to contend with Nature, and wrest from her some secret or some power which she had seen fit to withhold from mortal grasp. She loves to delude her aspiring students, and mock them with mysteries that seem but just beyond their utmost reach. To concoct new minerals, to produce new forms of vegetable life, to create an insect, if nothing higher in the living scale, is a sort of wish that has often revelled in the breast of a man of science. An astronomer, who lived far more among the distant worlds of space than in this lower sphere, recorded a wish to behold the opposite side of the moon, which, unless the system of the firmament be reversed, she can never turn towards the earth. On the same page of the volume was written the wish of a little child to have the stars for playthings.

The most ordinary wish, that was written down with wearisome recurrence, was, of course, for wealth, wealth, wealth, in sums from a few shillings up to unreckonable thousands. But in reality this often-repeated expression covered as many different desires. Wealth is the golden essence of the outward world, embodying almost everything that exists beyond the limits of the soul; and therefore it is the natural yearning for the life in the midst of which we find ourselves, and of which gold is the condition of enjoyment, that men abridge into this general wish. Here and there, it is true, the volume testified to some heart so perverted as to desire gold for its own sake. Many wished for power; a strange desire indeed, since it is but another form of slavery. Old people wished for the delights of youth; a fop, for a fashionable coat; an idle reader, for a new novel; a versifier, for a rhyme to some stubborn word; a painter, for Titian’s secret of coloring; a prince, for a cottage; a republican, for a kingdom and a palace; a libertine for his neighbor’s wife; a man of palate, for green peas; and a poor man, for a crust of bread. The ambitious desires of public men, elsewhere so craftily concealed, were here expressed openly and boldly, side by side with the unselfish wishes of the philanthropist for the welfare of the race, so beautiful, so comforting, in contrast with the egotism that continually weighed self against the world. Into the darker secrets of the Book of Wishes we will not penetrate.

It would be an instructive employment for a student of mankind, perusing this volume carefully and comparing its records with men’s perfected designs, as expressed in their deeds and daily life, to ascertain how far the one accorded with the other. Undoubtedly, in most cases, the correspondence would be found remote. The holy and generous wish, that rises like incense from a pure heart towards heaven, often lavishes its sweet perfume on the blast of evil times. The foul, selfish, murderous wish, that steams forth from a corrupted heart, often passes into the spiritual atmosphere without being concreted into an earthly deed. Yet this volume is probably truer, as a representation of the human heart, than is the living drama of action as it evolves around us. There is more of good and more of evil in it; more redeeming points of the bad and more errors of the virtuous; higher upsoarings, and baser degradation of the soul; in short, a more perplexing amalgamation of vice and virtue that we witness in the outward world. Decency and external conscience often produce a far fairer outside than is warranted by the stains within. And be it owned, on the other hand, that a man seldom repeats to his nearest friend, any more than he realizes in act, the purest wishes, which, at some blessed time or other, have arisen from the depths of his nature and witnessed for him in this volume. Yet there is enough on every leaf to make the good man shudder for his own wild and idle wishes, as well as for the sinner, whose whole life is the incarnation of a wicked desire.

But again the door is opened, and we hear the tumultuous stir of the world—a deep and awful sound, expressing in another form some portion of what is written in the volume that lies before the Man of Intelligence. A grandfatherly personage tottered hastily into the office, with such an earnestness in his infirm alacrity that his white hair floated backward as he hurried up to the desk, while his dim eyes caught a momentary lustre from his vehemence of purpose. This venerable figure explained that he was in search of To-Morrow.

“I have spent all my life in pursuit of it,” added the sage old gentleman, “being assured that To-Morrow has some vast benefit or other in store for me. But I am now getting a little in years, and must make haste; for, unless I overtake To-Morrow soon, I begin to be afraid it will finally escape me.”

“This fugitive To-Morrow, my venerable friend,” said the Man of Intelligence, “is a stray child of Time, and is flying from his father into the region of the infinite. Continue your pursuit, and you will doubtless come up with him; but as to the earthly gifts which you expect, he has scattered them all among a throng of Yesterdays.”

Obliged to content himself with this enigmatical response, the grandsire hastened forth with a quick clatter of his staff upon the floor; and, as he disappeared, a little boy scampered through the door in chase of a butterfly which had got astray amid the barren sunshine of the city. Had the old gentleman been shrewder, he might have detected To-Morrow under the semblance of that gaudy insect. The golden butterfly glistened through the shadowy apartment, and brushed its wings against the book of wishes, and fluttered forth again with the child still in pursuit.

A man now entered, in neglected attire, with the aspect of a thinker, but somewhat too rough-hewn and brawny for a scholar. His face was full of sturdy vigor, with some finer and keener attribute beneath. Though harsh at first, it was tempered with the glow of a large, warm heart, which had force enough to heat his powerful intellect through and through. He advanced to the Intelligencer and looked at him with a glance of such stern sincerity that perhaps few secrets were beyond its scope.

“I seek for Truth,” said he.

“It is precisely the most rare pursuit that has ever come under my cognizance,” replied the Intelligencer, as he made the new inscription in his volume. “Most men seek to impose some cunning falsehood upon themselves for truth. But I can lend no help to your researches. You must achieve the miracle for yourself. At some fortunate moment you may find Truth at your side, or perhaps she may be mistily discerned far in advance, or possibly behind you.”

“Not behind me,” said the seeker; “for I have left nothing on my track without a thorough investigation. She flits before me, passing now through a naked solitude, and now mingling with the throng of a popular assembly, and now writing with the pen of a French philosopher, and now standing at the altar of an old cathedral, in the guise of a Catholic priest, performing the high mass. Oh weary search! But I must not falter; and surely my heart-deep quest of Truth shall avail at last.”

He paused and fixed his eyes upon the Intelligencer with a depth of investigation that seemed to hold commerce with the inner nature of this being, wholly regardless of his external development.

“And what are you?” said he. “It will not satisfy me to point to this fantastic show of an Intelligence Office and this mockery of business. Tell me what is beneath it, and what your real agency in life, and your influence upon mankind.”

“Yours is a mind,” answered the Man of Intelligence, “before which the forms and fantasies that conceal the inner idea from the multitude vanish at once and leave the naked reality beneath. Know, then, the secret. My agency in worldly action, my connection with the press, and tumult, and intermingling, and development of human affairs, is merely delusive. The desire of man’s heart does for him whatever I seem to do. I am no minister of action, but the Recording Spirit.”

What further secrets were then spoken remains a mystery, inasmuch as the roar of the city, the bustle of human business, the outcry of the jostling masses, the rush and tumult of man’s life in its noisy and brief career, arose so high that it drowned the words of these two talkers; and whether they stood talking in the moon, or in Vanity Fair, or in a city of this actual world, is more than I can say.

@`

@#Little Ol’ You

@!Music Video: (a slight adaptation of an old Jim Reeves song)

@#Commentary on The Intelligence Office

~~

Matthew 5 ¶ 9 You have heard how it was said to them of old time: You shall not commit adultery. But I say unto you, that whosoever looks on a wife, lusting after her, has committed adultery with her already in his heart.

Matthew 13 ¶ 10 Again the kingdom of heaven is like unto a merchant that seeks good pearls, which when he had found one precious pearl, went and sold all that he had, and bought it.

@`

@~

@@(Twice-Told Tales, by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Companay. The Riverside Press, Cambridge. 1886)

@#ENDICOTT AND THE RED CROSS.

@@Nathaniel Hawthorne

At noon of an autumnal day, more than two centuries ago the English colors were displayed by the standard-bearer of the Salem trainband, which had mustered for martial exercise under the orders of John Endicott. It was a period when the religious exiles were accustomed often to buckle on their armor, and practice the handling of their weapons of war. Since the first settlement of New England, its prospects had never been so dismal. The dissensions between Charles the First and his subjects were then, and for several year afterwards, confined to the floor of Parliament. The measures of the King and ministry were rendered more tyrannically violent by an opposition, which had not yet acquired sufficient confidence in its own strength to resist royal injustice with the sword. The bigoted and haughty primate, Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, controlled the religious affairs of the realm, and was consequently invested with powers which might have wrought the utter ruin of the two Puritan colonies, Plymouth and Massachusetts. There is evidence on record that our forefathers perceived their danger, but were resolved that their infant country should not fall without a struggle, even beneath the giant strength of the King’s right arm.

Such was the aspect of the times when the folds of the English banner, with the Red Cross in its field, were flung out over a company of Puritans. Their leader, the famous Endicott, was a man of stern and resolute countenance, the effect of which was heightened by a grizzled beard that swept the upper portion of his breastplate. This piece of armor was so highly polished that the whole surrounding scene had its image in the glittering steel. The central object in the mirrored picture was an edifice of humble architecture with neither steeple nor bell to proclaim it—what nevertheless it was—the house of prayer. A token of the perils of the wilderness was seen in the grim head of a wolf, which had just been slain within the precincts of the town, and according to the regular mode of claiming the bounty, was nailed on the porch of the meeting-house. The blood was still plashing on the doorstep. There happened to be visible, at the same noontide hour, so many other characteristics of the times and manners of the Puritans, that we must endeavor to represent them in a sketch, though far less vividly that they were reflected in the polished breastplate of John Endicott.

In close vicinity to the sacred edifice appeared that important engine of Puritanic authority, the whipping-post—with the soil around it well trodden by the feet of evil doers, who had there been disciplined. At one corner of the meeting-house was the pillory, and at the other the stocks; and, by a singular good fortune for our sketch, the head of an Episcopalian and suspected Catholic was grotesquely incased in the former machine; while a fellow-criminal, who had boisterously quaffed a health to the king, was confined by the legs in the latter. Side by side, on the meeting-house steps, stood a male and a female figure. The man was a tall, lean, haggard personification of fanaticism, bearing on his breast this label,—A Wanton Gospeller—which betokened that he had dared to give interpretations of Holy Writ unsanctioned by the infallible judgment of the civil and religious rulers. His aspect showed no lack of zeal to maintain his heterodoxies, even at the stake. The woman wore a cleft stick on her tongue, in appropriate retribution for having wagged that unruly member against the elders of the church; and her countenance and gestures gave much cause to apprehend that, the moment the stick should be removed, a repetition of the offence would demand new ingenuity in chastising it.

The above-mentioned individuals had been sentenced to undergo their various modes of ignominy, for the space of one hour at noonday. But among the crowd were several whose punishment would be life-long; some, whose ears had been cropped, like those of puppy dogs; others, whose cheeks had been branded with the initials of their misdemeanors; one, with his nostrils slit and seared; and another, with a halter about his neck, which he was forbidden ever to take off, or to conceal beneath his garments. Methinks he must have been grievously tempted to affix the other end of the rope to some convenient beam or bough. There was likewise a young woman, with no mean share of beauty, whose doom it was to wear the letter A on the breast of her gown, in the eyes of all the world and her own children. And even her own children knew what that initial signified. Sporting with her infamy, the lost and desperate creature had embroidered the fatal token in scarlet cloth, with golden thread and the nicest art of needlework; so that the capital A might have been thought to mean Admirable, or anything rather than Adulteress.

Let not the reader argue, from any of these evidences of iniquity, that the times of the Puritans were more vicious than our own, when, as we pass along the very street of this sketch, we discern no badge of infamy on man or woman. It was the policy of our ancestors to search out even the most secret sins, and expose them to shame, without fear or favor, in the broadest light of the noonday sun. Were such the custom now, perchance we might find materials for a no less piquant sketch than the above.

Except the malefactors who we have described, and the diseased or infirm persons, the whole male population of the town, between sixteen years and sixty, were seen in the ranks of the trainband. A few stately savages, in all the pomp and dignity of the primeval Indian, stood gazing at the spectacle. Their flint-headed arrows were but childish weapons compared with the matchlocks of the Puritans, and would have rattled harmlessly against the steel caps and hammered iron breastplates which inclosed each soldier in an individual fortress. The valiant John Endicott glanced with an eye of pride at his sturdy followers, and prepared to renew the martial toils of the day.

“Come, my stout hearts!” quoth he, drawing his sword. “Let us show these poor heathen that we can handle our weapons like men of might. Well for them, if they put us not to prove it in earnest!”

The iron-breasted company straightened their line, and each man drew the heavy butt of his matchlock close to his left foot, thus awaiting the orders of the captain. But as Endicott glanced right and left along the front, he discovered a personage at some little distance with whom it behooved him to hold a parley. It was an elderly gentleman, wearing a black cloak and band, and a high-crowned hat, beneath which was a velvet skull-camp the whole being the garb of a Puritan minister. This reverend person bore a staff which seemed to have been recently cut in the forest, and his shoes were bemired a if he had been travelling on foot through the swamps of the wilderness. His aspect was perfectly that of a pilgrim, heightened also by an apostolic dignity. Just as Endicott perceived him he laid aside his staff, and stooped to drink at a bubbling fountain which gushed into the sunshine about a score of yards from the corner of the meeting-house. But, ere the good man drank, he turned his face heavenward in thankfulness, and then, holding back his gray beard with one hand, he scooped up his simple draught in the hollow of the other.

“What, ho! good Mr. Williams,” shouted Endicott. “You are welcome back again to our town of peace. How does our worthy Governor Winthrop? And what news from Boston?”

“The Governor hath his health, worshipful Sir,” answered Roger Williams, now resuming his staff, and drawing near. “And for the news, here is a letter, which, knowing I was to travel hitherward to-day, his Excellency committed to my charge. Belike it contains tidings of much import; for a ship arrived yesterday from England.”

Mr. Williams, the minister of Salem and of course known to all the spectators, had now reached the spot where Endicott was standing under the banner of his company, and put the Governor’s epistle into his hand. The broad seal was impressed with Winthrop’s coat of arms. Endicott hastily unclosed the letter and began to read, while, as his eye passed down the page, a wrathful change came over his manly countenance. The blood glowed through it, till it seemed to be kindling with an internal heat; nor was it unnatural to suppose that his breastplate would likewise become red-hot with the angry fire of the bosom which it covered. Arriving at the conclusion, he shook the letter fiercely in his hand, so that it rustled as loud as the flag above his head.

“Black tidings these, Mr. Williams,” said he; “blacker never came to New England. Doubtless you know their purport?”

“Yea, truly,” replied Roger Williams; “for the Governor consulted, respecting this matter, with my brethren in the ministry at Boston; and my opinion was likewise asked. And his Excellency entreats you by me, that the news be not suddenly noised abroad, lest the people be stirred up unto some outbreak, and thereby give the King and the Archbishop a handle against us.”

“The Governor is a wise man—a wise man, and a meek and moderate,” said Endicott, setting his teeth grimly. “Nevertheless, I must do according to my own best judgment. There is neither man, woman, nor child in New England, but has a concern as dear as life in these tiding; and if John Endicott’s voice be loud enough, man, woman, and child shall hear them. Soldiers, wheel into a hollow square! Ho, good people! Here are news for one and all of you.”

The soldiers closed in around their captain; and he and Roger Williams stood together under the banner of the Red Cross; while the women and the aged men pressed forward, and the mothers held up their children to look Endicott in the face. A few taps of the drum gave signal for silence and attention.

“Fellow-soldiers,—fellow-exiles,” began Endicott, speaking under strong excitement, yet powerfully restraining it, “wherefore did ye leave your native country? Wherefore, I say, have we left the green and fertile fields, the cottages, or, perchance, the old gray hall, where we were born and bred, the churchyards where our forefathers lie buried? Wherefore have we come hither to set up our own tombstones in a wilderness? A howling wilderness it is! The wolf and the bear meet us within halloo of our dwellings. The savage lieth in wait for us in the dismal shadow of the woods. The stubborn roots of the trees break our ploughshares, when we would till the earth. Our children cry for bread, and we must dig in the sands of the sea-shore to satisfy them. Wherefore, I say again, have we sought this country of a rugged soil and wintry sky? Was it not for the enjoyment of our civil rights? Was it not for liberty to worship God according to our conscience?”

“Call you this liberty of conscience?” interrupted a voice on the steps of the meeting-house.

It was the Wanton Gospeller. A sad and quiet smile flitted across the mild visage of Roger Williams. But Endicott, in the excitement of the moment, shook his sword wrathfully at the culprit—an ominous gesture from a man like him.

“What hast thou to do with conscience, thou knave?” cried he. “I said liberty to worship God, not license to profane and ridicule him. Break not in upon my speech, or I will lay thee neck and heels till this time to-morrow! Hearken to me, friends, nor heed that accursed rhapsodist. As I was saying, we have sacrificed all things, and have come to a land whereof the old world hath scarcely heard, that we might make a new world unto ourselves, and painfully seek a path from hence to heaven. But what think ye now? This son of a Scotch tyrant—this grandson of a Papistical and adulterous Scotch woman, whose death proved that a golden crown doth not always save an anointed head from the block,”—

“Nay, brother, nay,” interposed Mr. Williams; “thy words are not meet for a secret chamber, far less for a public street.”

“Hold thy peace, Roger Williams!” answered Endicott, imperiously. “My spirit is wiser than thine for the business now in hand. I tell ye, fellow-exiles, that Charles of England, and Laud, our bitterest persecutor, arch-priest of Canterbury, are resolute to pursue us even hither. They are taking counsel, saith this letter, to send over a governor-general, in whose breast shall be deposited all the law and equity of the land. They are minded, also, to establish the idolatrous forms of English Episcopacy; so that, when Laud shall kiss the Pope’s toe, as cardinal of Rome, he may deliver New England, bound hand and foot, into the power of his master!”

A deep groan from the auditors,—a sound of wrath, as well as fear and sorrow,—responded to this intelligence.

“Look ye to it, brethren,” resumed Endicott, with increasing energy. “If this king and this arch-prelate have their will, we shall briefly behold a cross on the spire of this tabernacle which we have builded, and a high altar within its walls, with wax tapers burning round it at noonday. We shall hear the sacring bell, and the voices of the Romish priests saying the mass. But think ye, Christian men, that these abominations may be suffered without a sword drawn? without a shot fired? without blood spilt, yea, on the very stairs of the pulpit? No,—be ye strong of hand and stout of heart! Here we stand on our own soil, which we have bought with our goods, which we have won with our swords, which we have cleared with our axes, which we have tilled with the sweat of our brows, which we have sanctified with our prayers to the God that brought us hither! Who shall enslave us here? What have we to do with this mitred prelate—with this crowned king? What have we to do with England?”

Endicott gazed round at the excited countenances of the people, now full of his own spirit, and then turned suddenly to the standard-bearer, who stood close behind him.

“Officer, lower your banner!” said he.

The officer obeyed; and, brandishing his sword, Endicott thrust it through the cloth, and, with his left hand, rent the Red Cross completely out of the banner. He then waved the tattered ensign above his head.

“Sacrilegious wretch!” cried the high-churchman in the pillory, unable longer to restrain himself, “thou hast rejected the symbol of our holy religion!”

“Treason, treason!” roared the royalist in the stocks. “He hath defaced the King’s banner!”

“Before God and man, I will avouch the deed,” answered Endicott. “Beat a flourish, drummer!—shout, soldiers and people!—in honor of the ensign of New England. Neither Pope nor Tyrant hath part in it now!”

With a cry of triumph, the people gave their sanction to one of the boldest exploits which our history records. And forever honored be the name of Endicott! We look back through the mist of ages, and recognize in the rending of the Red Cross from New England’s banner the first omen of that deliverance which our fathers consummated after the bones of the stern Puritan had lain more that a century in the dust.

@`

@#Commentary on Endicott and the Red Cross

~~

How delightful that in composition and execution of the story the results are perfect! The events of a single day in the distant past of over three hundred and fifty years becomes vividly real.

@`

@#  THE MAN OF ADAMANT

@~

@!An Apologue

@@by Nathaniel Hawthorne

In the old times of religious gloom and intolerance, lived Richard Digby, the gloomiest and most intolerant of a stern brotherhood. His plan of salvation was so narrow, that, like a plank in a tempestuous sea, it could avail no sinner but himself, who bestrode it triumphantly, and hurled anathemas against the wretches whom he saw struggling with the billows of eternal death. In his view of the matter, it was a most abominable crime—as, indeed, it is a great folly—for men to trust to their own strength, or even to grapple to any other fragment of the wreck, save this narrow plank, which, moreover, he took special care to keep out of their reach. In other words, as his creed was like no man’s else, and being well pleased that Providence had entrusted him, alone of mortals, with the treasure of a true faith, Richard Digby determined to seclude himself to the sole and constant enjoyment of his happy fortune.

‘And verily,’ thought he, ‘I deem it a chief condition of Heaven’s mercy to myself, that I hold no communion with those abominable myriads which it hath cast off to perish, Peradventure, were I to tarry longer in the tents of Kedar, the gracious boon would be revoked, and I also be swallowed up in the deluge of wrath, or consumed in the storm of fire and brimstone, or involved in whatever new kind of ruin is ordained for the horrible perversity of the generation.’

So Richard Digby took an axe, to hew space enough for a tabernacle in the wilderness, and some few other necessaries, especially a sword and gun, to smite and slay any intruder upon his hallowed seclusion; and plunged into the dreariest depths of the forest. On its verge, however, he paused a moment, to shake off the dust of his feet against the village where he had dwelt, and to invoke a curse on the meeting-house, which he regarded as a temple of heathen idolatry. He felt a curiosity, also, to see whether the fire and brimstone would not rush down from Heaven at once, now that the one righteous man had provided for his own safety. But, as the sunshine continued to fall peacefully on the cottages and fields, and the husbandmen labored and children played, and as there were many tokens of present happiness, and nothing ominous of a speedy judgment, he turned away, somewhat disappointed. The further he went, however, and the lonelier he felt himself, and the thicker the trees stood along his path, and the darker the shadow overhead, so much the more did Richard Digby exult. He talked to himself, as he strode onward; he read his Bible to himself, as he sat beneath the trees; and, as the gloom of the forest hid the blessed sky, I had almost added, that, at morning, noon, and eventide, he prayed to himself. So congenial was this mode of life to his disposition, that he often laughed to himself, but was displeased when an echo tossed him back the long, loud roar.

In this manner, he journeyed onward three days and two nights, and came, on the third evening, to the mouth of a cave, which, at first sight, reminded him of Elijah’s cave at Horeb, though perhaps it more resembled Abraham’s sepulchral cave, at Machpelah. It entered into the heart of a rocky hill. There was so dense a veil of tangled foliage about it, that none but a sworn lover of gloomy recesses would have discovered the low arch of its entrance, or have dared to step within its vaulted chamber, where the burning eyes of a panther might encounter him. If Nature meant this remote and dismal cavern for the use of man, it could only be, to bury in its gloom the victims of a pestilence, and then to block up its mouth with stones, and avoid the spot forever after. There was nothing bright nor cheerful near it, except a bubbling fountain, some twenty paces off, at which Richard Digby hardly threw away a glance. But he thrust his head into the cave, shivered, and congratulated himself.

~@The finger of Providence hath pointed my way!…

‘The finger of Providence hath pointed my way!’ cried he, aloud, while the tomb-like den returned a strange echo, as if some one within were mocking him. ‘Here my soul will be at peace; for the wicked will not find me. Here I can read the Scriptures, and be no more provoked with lying interpretations. Here I can offer up acceptable prayers, because my voice will not be mingled with the sinful supplications of the multitude. Of a truth, the only way to Heaven leadeth through the narrow entrance of this cave—and I alone have found it!’

THE MAN OF ADAMANT

@~

@!An Apologue

@@by Nathaniel Hawthorne

In the old times of religious gloom and intolerance, lived Richard Digby, the gloomiest and most intolerant of a stern brotherhood. His plan of salvation was so narrow, that, like a plank in a tempestuous sea, it could avail no sinner but himself, who bestrode it triumphantly, and hurled anathemas against the wretches whom he saw struggling with the billows of eternal death. In his view of the matter, it was a most abominable crime—as, indeed, it is a great folly—for men to trust to their own strength, or even to grapple to any other fragment of the wreck, save this narrow plank, which, moreover, he took special care to keep out of their reach. In other words, as his creed was like no man’s else, and being well pleased that Providence had entrusted him, alone of mortals, with the treasure of a true faith, Richard Digby determined to seclude himself to the sole and constant enjoyment of his happy fortune.

‘And verily,’ thought he, ‘I deem it a chief condition of Heaven’s mercy to myself, that I hold no communion with those abominable myriads which it hath cast off to perish, Peradventure, were I to tarry longer in the tents of Kedar, the gracious boon would be revoked, and I also be swallowed up in the deluge of wrath, or consumed in the storm of fire and brimstone, or involved in whatever new kind of ruin is ordained for the horrible perversity of the generation.’

So Richard Digby took an axe, to hew space enough for a tabernacle in the wilderness, and some few other necessaries, especially a sword and gun, to smite and slay any intruder upon his hallowed seclusion; and plunged into the dreariest depths of the forest. On its verge, however, he paused a moment, to shake off the dust of his feet against the village where he had dwelt, and to invoke a curse on the meeting-house, which he regarded as a temple of heathen idolatry. He felt a curiosity, also, to see whether the fire and brimstone would not rush down from Heaven at once, now that the one righteous man had provided for his own safety. But, as the sunshine continued to fall peacefully on the cottages and fields, and the husbandmen labored and children played, and as there were many tokens of present happiness, and nothing ominous of a speedy judgment, he turned away, somewhat disappointed. The further he went, however, and the lonelier he felt himself, and the thicker the trees stood along his path, and the darker the shadow overhead, so much the more did Richard Digby exult. He talked to himself, as he strode onward; he read his Bible to himself, as he sat beneath the trees; and, as the gloom of the forest hid the blessed sky, I had almost added, that, at morning, noon, and eventide, he prayed to himself. So congenial was this mode of life to his disposition, that he often laughed to himself, but was displeased when an echo tossed him back the long, loud roar.

In this manner, he journeyed onward three days and two nights, and came, on the third evening, to the mouth of a cave, which, at first sight, reminded him of Elijah’s cave at Horeb, though perhaps it more resembled Abraham’s sepulchral cave, at Machpelah. It entered into the heart of a rocky hill. There was so dense a veil of tangled foliage about it, that none but a sworn lover of gloomy recesses would have discovered the low arch of its entrance, or have dared to step within its vaulted chamber, where the burning eyes of a panther might encounter him. If Nature meant this remote and dismal cavern for the use of man, it could only be, to bury in its gloom the victims of a pestilence, and then to block up its mouth with stones, and avoid the spot forever after. There was nothing bright nor cheerful near it, except a bubbling fountain, some twenty paces off, at which Richard Digby hardly threw away a glance. But he thrust his head into the cave, shivered, and congratulated himself.

~@The finger of Providence hath pointed my way!…

‘The finger of Providence hath pointed my way!’ cried he, aloud, while the tomb-like den returned a strange echo, as if some one within were mocking him. ‘Here my soul will be at peace; for the wicked will not find me. Here I can read the Scriptures, and be no more provoked with lying interpretations. Here I can offer up acceptable prayers, because my voice will not be mingled with the sinful supplications of the multitude. Of a truth, the only way to Heaven leadeth through the narrow entrance of this cave—and I alone have found it!’

In regard to this cave, it was observable that the roof, so far as the imperfect light permitted it to be seen, was hung with substances resembling opaque icicles; for the damps of unknown centuries, dripping down continually, had become as hard as adamant; and wherever that moisture fell, it seemed to possess the power of converting what it bathed to stone. The fallen leaves and sprigs of foliage, which the wind had swept into the cave, and the little feathery shrubs, rooted near the threshold, were not wet with a natural dew, but had been embalmed by this wondrous process. And here I am put in mind, that Richard Digby, before he withdrew himself from the world, was supposed by skilful physicians to have contracted a disease, for which no remedy was written in their medical books. It was a deposition of calculus particles within his heart, caused by an obstructed circulation of the blood, and unless a miracle should be wrought for him, there was danger that the malady might act on the entire substance of the organ, and change his fleshly heart to stone. Many, indeed, affirmed that the process was already near its consummation. Richard Digby, however, could never be convinced that any such direful work was going on within him; nor when he saw the sprigs of marble foliage, did his heart even throb the quicker, at the similitude suggested by these once tender herbs. It may be, that this same insensibility was a symptom of the disease.

Be that as it might, Richard Digby was well contented with his sepulchral cave. So dearly did he love this congenial spot, that, instead of going a few paces to the bubbling spring for water, he allayed his thirst with now and then a drop of moisture from the roof, which, had it fallen any where but on his tongue, would have been congealed into a pebble. For a man predisposed to stoniness of the heart, this surely was unwholesome liquor. But there he dwelt, for three days more, eating herbs and roots, drinking his own destruction, sleeping, as it were, in a tomb, and awaking to the solitude of death, yet esteeming this horrible mode of life as hardly inferior to celestial bliss. Perhaps superior; for, above the sky, there would be angels to disturb him. At the close of the third day, he sat in the portal of his mansion, reading the Bible aloud, because no other ear could profit by it, and reading it amiss, because the rays of the setting sun did not penetrate the dismal depth of shadow roundabout him, nor fall upon the sacred page. Suddenly, however, a faint gleam of light was thrown over the volume, and raising his eyes, Richard Digby saw that a young woman stood before the mouth of the cave, and that the sunbeams bathed her white garment, which thus seemed to possess a radiance of its own.

~@‘Good evening, Richard,’ said the girl, ‘I have come from afar to find thee.’

‘Good evening, Richard,’ said the girl, ‘I have come from afar to find thee.’

The slender grace and gentle loveliness of this young woman were at once recognized by Richard Digby. Her name was Mary Goffe. She had been a convert to his preaching of the word in England, before he yielded himself to that exclusive bigotry, which now enfolded him with such an iron grasp, that no other sentiment could reach his bosom. When he came a pilgrim to America, she had remained in her father’s hall, but now, as it appeared, had crossed the ocean after him, impelled by the same faith that led other exiles hither, and perhaps by love almost as holy. What else but faith and love united could have sustained so delicate a creature, wandering thus far into the forest, with her golden hair disheveled by the boughs, and her feet wounded by the thorns! Yet, weary and faint though she must have been, and affrighted at the dreariness of the cave, she looked on the lonely man with a mild and pitying expression, such as might beam from an angels eyes, towards an afflicted mortal. But the recluse, frowning sternly upon her, and keeping his finger between the leaves of his half closed Bible, motioned her away with his hand.

~@The slender grace and gentle loveliness of this young woman…

‘Off!’ cried he. ‘I am sanctified, and thou art sinful. Away!’

‘Oh, Richard,’ said she, earnestly, ‘I have come this weary way, because I heard that a grievous distemper had seized upon thy heart; and a great Physician hath given me the skill to cure it. There is no other remedy than this which I have brought thee. Turn me not away, therefore, nor refuse my medicine; for then must this dismal cave be thy sepulchre.’

In regard to this cave, it was observable that the roof, so far as the imperfect light permitted it to be seen, was hung with substances resembling opaque icicles; for the damps of unknown centuries, dripping down continually, had become as hard as adamant; and wherever that moisture fell, it seemed to possess the power of converting what it bathed to stone. The fallen leaves and sprigs of foliage, which the wind had swept into the cave, and the little feathery shrubs, rooted near the threshold, were not wet with a natural dew, but had been embalmed by this wondrous process. And here I am put in mind, that Richard Digby, before he withdrew himself from the world, was supposed by skilful physicians to have contracted a disease, for which no remedy was written in their medical books. It was a deposition of calculus particles within his heart, caused by an obstructed circulation of the blood, and unless a miracle should be wrought for him, there was danger that the malady might act on the entire substance of the organ, and change his fleshly heart to stone. Many, indeed, affirmed that the process was already near its consummation. Richard Digby, however, could never be convinced that any such direful work was going on within him; nor when he saw the sprigs of marble foliage, did his heart even throb the quicker, at the similitude suggested by these once tender herbs. It may be, that this same insensibility was a symptom of the disease.

Be that as it might, Richard Digby was well contented with his sepulchral cave. So dearly did he love this congenial spot, that, instead of going a few paces to the bubbling spring for water, he allayed his thirst with now and then a drop of moisture from the roof, which, had it fallen any where but on his tongue, would have been congealed into a pebble. For a man predisposed to stoniness of the heart, this surely was unwholesome liquor. But there he dwelt, for three days more, eating herbs and roots, drinking his own destruction, sleeping, as it were, in a tomb, and awaking to the solitude of death, yet esteeming this horrible mode of life as hardly inferior to celestial bliss. Perhaps superior; for, above the sky, there would be angels to disturb him. At the close of the third day, he sat in the portal of his mansion, reading the Bible aloud, because no other ear could profit by it, and reading it amiss, because the rays of the setting sun did not penetrate the dismal depth of shadow roundabout him, nor fall upon the sacred page. Suddenly, however, a faint gleam of light was thrown over the volume, and raising his eyes, Richard Digby saw that a young woman stood before the mouth of the cave, and that the sunbeams bathed her white garment, which thus seemed to possess a radiance of its own.

~@‘Good evening, Richard,’ said the girl, ‘I have come from afar to find thee.’

‘Good evening, Richard,’ said the girl, ‘I have come from afar to find thee.’

The slender grace and gentle loveliness of this young woman were at once recognized by Richard Digby. Her name was Mary Goffe. She had been a convert to his preaching of the word in England, before he yielded himself to that exclusive bigotry, which now enfolded him with such an iron grasp, that no other sentiment could reach his bosom. When he came a pilgrim to America, she had remained in her father’s hall, but now, as it appeared, had crossed the ocean after him, impelled by the same faith that led other exiles hither, and perhaps by love almost as holy. What else but faith and love united could have sustained so delicate a creature, wandering thus far into the forest, with her golden hair disheveled by the boughs, and her feet wounded by the thorns! Yet, weary and faint though she must have been, and affrighted at the dreariness of the cave, she looked on the lonely man with a mild and pitying expression, such as might beam from an angels eyes, towards an afflicted mortal. But the recluse, frowning sternly upon her, and keeping his finger between the leaves of his half closed Bible, motioned her away with his hand.

~@The slender grace and gentle loveliness of this young woman…

‘Off!’ cried he. ‘I am sanctified, and thou art sinful. Away!’

‘Oh, Richard,’ said she, earnestly, ‘I have come this weary way, because I heard that a grievous distemper had seized upon thy heart; and a great Physician hath given me the skill to cure it. There is no other remedy than this which I have brought thee. Turn me not away, therefore, nor refuse my medicine; for then must this dismal cave be thy sepulchre.’

‘Away!’ replied Richard Digby, still with a dark frown. ‘My heart is in better condition than thine own. Leave me, earthly one; for the sun is almost set; and when no light reaches the door of the cave, then is my prayer time!’

Now, great as was her need, Mary Goffe did not plead with this stony hearted man for shelter and protection, nor ask any thing whatever for her own sake. All her zeal was for his welfare.

‘Come back with me!’ she exclaimed, clasping her hands—‘Come back to thy fellow men; for they need thee, Richard; and thou hast tenfold need of them. Stay not in this evil den; for the air is chill, and the damps are fatal; nor will any, that perish within it, ever find the path to Heaven. Hasten hence, I entreat thee, for thine own soul’s sake; for either the roof will fall upon thy head, or some other speedy destruction is at hand.’

‘Perverse woman!’ answered Richard Digby, laughing aloud; for he was moved to bitter mirth by her foolish vehemence. ‘I tell thee that the path to Heaven leadeth straight through this narrow portal, where I sit. And, moreover, the destruction thou speakest of, is ordained, not for this blessed cave, but for all other habitations of mankind, throughout the earth. Get thee hence speedily, that thou may’st have thy share!’

So saying, he opened his Bible again, and fixed his eyes intently on the page, being resolved to withdraw his thoughts from this child of sin and wrath, and to waste no more of his holy breath upon her. The shadow had now grown so deep, where he was sitting, that he made continual mistakes in what he read, converting all that was gracious and merciful, to denunciations of vengeance and unutterable woe, on every created being but himself. Mary Goffe, meanwhile, was leaning against a tree, beside the sepulchral cave, very sad, yet with something heavenly and ethereal in her unselfish sorrow. The light from the setting sun still glorified her form, and was reflected a little way within the darksome den, discovering so terrible a gloom, that the maiden shuddered for its self-doomed inhabitant. Espying the bright fountain near at hand, she hastened thither, and scooped up a portioin of its water, in a cup of birchen bark. A few tears mingled with the draught, and perhaps gave it all its efficacy. She then returned to the mouth of the cave, and knelt down at Richard Digby’s feet.

‘Richard,’ she said, with passionate fervor, yet a gentleness in all her passion, ‘I pray thee, by thy hope of Heaven, and as thou wouldst not dwell in this tomb forever, drink of this hallowed water, be it but a single drop! Then, make room for me by thy side, and let us read together one page of that blessed volume—and, lastly, kneel down with me and pray! Do this; and thy stony heart shall become softer than a babe’s, and all be well.’

But Richard Digby, in utter abhorrence of the proposal, cast the Bible at his feet, and eyed her with such a fixed and evil frown, that he looked less like a living man than a marble statue, wrought by some dark imagined sculptor to express the most repulsive mood that human features could assume. And, as his look grew even devilish, so, with an equal change, did Mary Goffe become more sad, more mild, more pitiful, more like a sorrowing angel. But, the more heavenly she was the more hateful did she seem to Richard Digby, who at length raised his hand, and smote down the cup of hallowed water upon the threshold of the cave, thus rejecting the only medicine that could have cured his stony heart. A sweet perfume lingered in the air for a moment, and then was gone.

‘Tempt me no more, accursed woman,’ exclaimed he, still with his marble frown, ‘lest I smite thee down also! What hast thou to do with my Bible?—what with my prayers?—what with my Heaven’

~@And either it was her ghost that haunted the wild forest, or else a dreamlike spirit, typifying pure Religion.

No sooner had he spoken these dreadful words, than Richard Digby’s heart ceased to beat; while—so the legend says—the form of Mary Goffe melted into the last sunbeams, and returned from the sepulchral cave to Heaven. For Mary Goffe had been buried in an English churchyard, months before; and either it was her ghost that haunted the wild forest, or else a dreamlike spirit, typifying pure Religion.

Above a century afterwards, when the trackless forest of Richard Digby’s day had long been interspersed with settlements, the children of a neighboring farmer were playing at the foot of a hill. The trees, on account of the rude and broken surface of this acclivity, had never been felled, and were crowded so densely together, as to hide all but a few rocky prominences, wherever their roots could grapple with the soil. A little boy and girl, to conceal themselves from their playmates, had crept into the deepest shade, where not only the darksome pines, but a thick veil of creeping plants suspended from an overhanging rock, combined to make a twilight at noonday, and almost a midnight at all other seasons. There the children hid themselves, and shouted, repeating the cry at intervals, till the whole party of pursuers were drawn thither, and pulling aside the matted foliage, let in a doubtful glimpse of daylight. But scarcely was this accomplished, when the little group uttered a simultaneous shriek and tumbled headlong down the hill, making the best of their way homeward, without a second glance into the gloomy recess. Their father, unable to comprehend what had so startled them, took his axe, and by felling one or two trees, and tearing away the creeping plants, laid the mystery open to the day. He had discovered the entrance of a cave, closely resembling the mouth of a sepulchre, within which sat the figure of a man, whose gesture and attitude warned the father and children to stand back, while his visage wore a most forbidding frown. This repulsive personage seemed to have been carved in the same gray stone that formed the walls and portal of the cave. On minuter inspection, indeed, such blemishes were observed, as made it doubtful whether the figure were really a statue, chiselled by human art, and somewhat worn and defaced by the lapse of ages, or a freak of Nature, who might have chosen to imitate, in stone, her usual handiwork of flesh. Perhaps it was the least unreasonable idea, suggested by this strange spectacle, that the moisture of the cave possessed a petrifying quality, which had thus awfully embalmed a human corpse.

There was something so frightful in the aspect of this Man of Adamant, that the farmer, the moment that he recovered from the fascination of his first gaze, began to heap stones into the mouth of the cavern. His wife, who had followed him to the hill, assisted her husband’s efforts. The children, also, approached as near as they durst, with their little hands full of pebbles, and cast them on the pile. Earth was then thrown into the crevices, and the whole fabric overlaid with sods. Thus all traces of the discovery were obliterated, leaving only a marvelous legend, which grew wilder from one generation to another, as the children told it to their grandchildren, and they to their posterity, till few believed that there had ever been a cavern or a statue, where now they saw but a grassy patch on the shadowy hill-side. Yet, grown people avoid the spot, nor do children play there. Friendship, and Love, and Piety, all human and celestial sympathies, should keep aloof from the hidden cave; for there still sits, and, unless an earthquake crumble down the roof upon his head, shall sit forever, the shape of Richard Digby, in the attitude of repelling the whole race of mortals—not from Heaven—but from the horrible loneliness of his dark, cold sepulchre.

@`

‘Away!’ replied Richard Digby, still with a dark frown. ‘My heart is in better condition than thine own. Leave me, earthly one; for the sun is almost set; and when no light reaches the door of the cave, then is my prayer time!’

Now, great as was her need, Mary Goffe did not plead with this stony hearted man for shelter and protection, nor ask any thing whatever for her own sake. All her zeal was for his welfare.

‘Come back with me!’ she exclaimed, clasping her hands—‘Come back to thy fellow men; for they need thee, Richard; and thou hast tenfold need of them. Stay not in this evil den; for the air is chill, and the damps are fatal; nor will any, that perish within it, ever find the path to Heaven. Hasten hence, I entreat thee, for thine own soul’s sake; for either the roof will fall upon thy head, or some other speedy destruction is at hand.’

‘Perverse woman!’ answered Richard Digby, laughing aloud; for he was moved to bitter mirth by her foolish vehemence. ‘I tell thee that the path to Heaven leadeth straight through this narrow portal, where I sit. And, moreover, the destruction thou speakest of, is ordained, not for this blessed cave, but for all other habitations of mankind, throughout the earth. Get thee hence speedily, that thou may’st have thy share!’

So saying, he opened his Bible again, and fixed his eyes intently on the page, being resolved to withdraw his thoughts from this child of sin and wrath, and to waste no more of his holy breath upon her. The shadow had now grown so deep, where he was sitting, that he made continual mistakes in what he read, converting all that was gracious and merciful, to denunciations of vengeance and unutterable woe, on every created being but himself. Mary Goffe, meanwhile, was leaning against a tree, beside the sepulchral cave, very sad, yet with something heavenly and ethereal in her unselfish sorrow. The light from the setting sun still glorified her form, and was reflected a little way within the darksome den, discovering so terrible a gloom, that the maiden shuddered for its self-doomed inhabitant. Espying the bright fountain near at hand, she hastened thither, and scooped up a portioin of its water, in a cup of birchen bark. A few tears mingled with the draught, and perhaps gave it all its efficacy. She then returned to the mouth of the cave, and knelt down at Richard Digby’s feet.

‘Richard,’ she said, with passionate fervor, yet a gentleness in all her passion, ‘I pray thee, by thy hope of Heaven, and as thou wouldst not dwell in this tomb forever, drink of this hallowed water, be it but a single drop! Then, make room for me by thy side, and let us read together one page of that blessed volume—and, lastly, kneel down with me and pray! Do this; and thy stony heart shall become softer than a babe’s, and all be well.’

But Richard Digby, in utter abhorrence of the proposal, cast the Bible at his feet, and eyed her with such a fixed and evil frown, that he looked less like a living man than a marble statue, wrought by some dark imagined sculptor to express the most repulsive mood that human features could assume. And, as his look grew even devilish, so, with an equal change, did Mary Goffe become more sad, more mild, more pitiful, more like a sorrowing angel. But, the more heavenly she was the more hateful did she seem to Richard Digby, who at length raised his hand, and smote down the cup of hallowed water upon the threshold of the cave, thus rejecting the only medicine that could have cured his stony heart. A sweet perfume lingered in the air for a moment, and then was gone.

‘Tempt me no more, accursed woman,’ exclaimed he, still with his marble frown, ‘lest I smite thee down also! What hast thou to do with my Bible?—what with my prayers?—what with my Heaven’

~@And either it was her ghost that haunted the wild forest, or else a dreamlike spirit, typifying pure Religion.

No sooner had he spoken these dreadful words, than Richard Digby’s heart ceased to beat; while—so the legend says—the form of Mary Goffe melted into the last sunbeams, and returned from the sepulchral cave to Heaven. For Mary Goffe had been buried in an English churchyard, months before; and either it was her ghost that haunted the wild forest, or else a dreamlike spirit, typifying pure Religion.

Above a century afterwards, when the trackless forest of Richard Digby’s day had long been interspersed with settlements, the children of a neighboring farmer were playing at the foot of a hill. The trees, on account of the rude and broken surface of this acclivity, had never been felled, and were crowded so densely together, as to hide all but a few rocky prominences, wherever their roots could grapple with the soil. A little boy and girl, to conceal themselves from their playmates, had crept into the deepest shade, where not only the darksome pines, but a thick veil of creeping plants suspended from an overhanging rock, combined to make a twilight at noonday, and almost a midnight at all other seasons. There the children hid themselves, and shouted, repeating the cry at intervals, till the whole party of pursuers were drawn thither, and pulling aside the matted foliage, let in a doubtful glimpse of daylight. But scarcely was this accomplished, when the little group uttered a simultaneous shriek and tumbled headlong down the hill, making the best of their way homeward, without a second glance into the gloomy recess. Their father, unable to comprehend what had so startled them, took his axe, and by felling one or two trees, and tearing away the creeping plants, laid the mystery open to the day. He had discovered the entrance of a cave, closely resembling the mouth of a sepulchre, within which sat the figure of a man, whose gesture and attitude warned the father and children to stand back, while his visage wore a most forbidding frown. This repulsive personage seemed to have been carved in the same gray stone that formed the walls and portal of the cave. On minuter inspection, indeed, such blemishes were observed, as made it doubtful whether the figure were really a statue, chiselled by human art, and somewhat worn and defaced by the lapse of ages, or a freak of Nature, who might have chosen to imitate, in stone, her usual handiwork of flesh. Perhaps it was the least unreasonable idea, suggested by this strange spectacle, that the moisture of the cave possessed a petrifying quality, which had thus awfully embalmed a human corpse.